Sherwood Anderson A Story Teller's Story Download UPDATED

Sherwood Anderson A Story Teller's Story Download

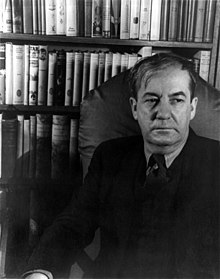

| Sherwood Anderson | |

|---|---|

Anderson in 1933 | |

| Born | (1876-09-xiii)September 13, 1876 Camden, Ohio, U.s. |

| Died | March 8, 1941(1941-03-08) (aged 64) Colón, Panama |

| Occupation | Author |

| Notable works | Winesburg, Ohio |

| Spouse | Cornelia Pratt Lane (1904–1916) Tennessee Claflin Mitchell (1916–1924) Elizabeth Prall (1924–1932) Eleanor Copenhaver (1933–1941) |

| Signature | |

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and curt story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and Elyria, Ohio. In 1912, Anderson had a nervous breakdown that led him to carelessness his business organisation and family to become a writer.

At the time, he moved to Chicago and was somewhen married three additional times. His about indelible work is the brusque-story sequence Winesburg, Ohio, [1] which launched his career. Throughout the 1920s, Anderson published several curt story collections, novels, memoirs, books of essays, and a book of poetry. Though his books sold reasonably well, Dark Laughter (1925), a novel inspired by Anderson'south time in New Orleans during the 1920s, was his but bestseller.

Early life [edit]

Sherwood Berton Anderson was built-in on September 13, 1876, at 142 S. Lafayette Street in Camden, Ohio,[2] a farming town with a population of around 650 (co-ordinate to the 1870 census).[3] He was the 3rd of seven children born to Emma Jane (née Smith) and old Wedlock soldier and harness-maker Irwin McLain Anderson. Considered reasonably well-off financially, Anderson's father was seen as an upwards-and-comer by his Camden contemporaries,[3] and the family left town merely before Sherwood'southward first birthday. Reasons for the divergence are uncertain; most biographers note rumors of debts incurred past either Irwin[4] [5] or his brother Benjamin.[3] The Andersons headed n to Caledonia by way of a cursory stay in a hamlet of a few hundred called Independence (at present Butler). Four[6] or five[7] years were spent in Caledonia, years that formed Anderson's primeval memories. This menses later inspired his semi-autobiographical novel Tar: A Midwest Babyhood (1926).[8] In Caledonia Anderson's male parent began drinking excessively, which led to financial difficulties, somewhen causing the family to leave the town.[eight]

With each motion, Irwin Anderson's prospects dimmed; while in Camden he was the proprietor of a successful shop and could employ an assistant, just past the time the Andersons finally settled down in Clyde, Ohio, in 1884, Irwin could get work only as a hired man to harness manufacturers.[9] That task was short-lived, and for the rest of Sherwood Anderson'southward childhood, his father barely supported the family equally an occasional sign-painter and paperhanger, while his mother took in washing to make ends run into.[10] Partly every bit a result of these misfortunes, young Sherwood became adept at finding various odd jobs to help his family, earning the nickname "Jobby".[11] [12]

Though he was a decent student, Anderson'southward attendance at school declined as he began picking upward work, and he finally left school for good at age fourteen after about ix months of high schoolhouse.[13] [xiv] From the time he began to cut schoolhouse to the time he left boondocks, Anderson worked as a "newsboy, errand boy, waterboy, moo-cow-commuter, stable groom, and maybe printer's devil, non to mention banana to Irwin Anderson, Sign Painter",[13] in addition to assembling bicycles for the Elmore Manufacturing Company.[15] Even in his teens, Anderson'due south talent for selling was evident, a talent he would later describe on in a successful career in ad. As a newsboy he was said to have convinced a tired farmer in a saloon to buy 2 copies of the same evening paper.[12] With the exception of work, Anderson'due south childhood resembled that of other boys his age.[ citation needed ]

In add-on to participating in local events and spending fourth dimension with his friends, Anderson was a voracious reader. Though in that location were only a few books in the Anderson home,[xiii] the youth read widely by borrowing from the schoolhouse library (there was not a public library in Clyde until 1903), and the personal libraries of a school superintendent and of John Tichenor, a local artist, who responded to Anderson'south interest.[sixteen]

Past Anderson'due south 18th twelvemonth in 1895, his family was on shaky ground. His male parent had started to disappear for weeks.[17] Ii years before, in 1893, Karl, Sherwood'south elder blood brother, had left Clyde for Chicago.[eighteen] On May 10, 1895, his mother succumbed to tuberculosis. Sherwood, now essentially on his own, boarded at the Harvey & Yetter'southward livery stable where he worked as a groom—an feel that would interpret into several of his best-known stories.[19] [20] (Irwin Anderson died in 1919 after having been estranged from his son for ii decades.)[21] Two months before his mother's death, in March 1895, Anderson had signed up with the Ohio National Baby-sit for a five-year hitch,[22] while he was going steady with Bertha Baynes, an attractive girl and possibly the inspiration for Helen White in Winesburg, Ohio,[23] and he was working a secure job at the cycle manufacturing plant. But his mother'due south death precipitated his leaving Clyde.[21] He settled in Chicago around late 1896[24] [25] or the spring or summer of 1897, having worked a few small-scale-town factory jobs forth the way.[26]

Chicago and state of war [edit]

Anderson moved to a boardinghouse in Chicago owned by a one-time mayor of Clyde. His brother Karl lived in the metropolis and was studying at the Fine art Establish. Anderson moved in with him and quickly found a job at a cold-storage plant.[27] In belatedly 1897, Karl moved away, and Anderson relocated to a two-room flat with his sis and two younger brothers newly come from Clyde.[28] Coin was tight—Anderson earned "two dollars for a day of ten hours"—[29] but with occasional support from Karl, they got past. Following the instance of his Clyde confederate and lifelong friend Cliff Paden (later to get known as John Emerson) and Karl, Anderson took up the thought of furthering his educational activity by enrolling in night school at the Lewis Institute.[30] He attended several classes regularly including "New Business Arithmetic" earning marks that placed him second in the class.[31] Information technology was also there that Anderson heard lectures on Robert Browning and was perchance outset introduced to the poetry of Walt Whitman.[30] Soon, still, Anderson'due south starting time stint in Chicago would come to an end as the U.s. prepared to enter the Castilian–American War.

Although he had limited resource while in Chicago, Anderson bought a new suit and returned to Clyde to join the military.[32] Once home, the company he joined mustered into the regular army at Camp Bushnell, Ohio on May 12, 1898.[33] Several months of grooming followed at diverse southern encampments until early in 1899, when his visitor was sent to Republic of cuba. Fighting had ceased iv months prior to their arrival. On April 21, 1899, they left Cuba having seen no gainsay.[34] According to Irving Howe, "Sherwood was popular among his ground forces comrades, who remembered him every bit a swain given to prolonged reading, more often than not in dime westerns and historical romances, and talented at finding a girl when he wanted one. For the beginning of these traits he was frequently teased, but the second brought him the respect it normally does in armies."[35]

After the war, Anderson resided briefly in Clyde performing agricultural work before deciding to return to school.[36] In September 1899 Anderson joined his siblings Karl and Stella in Springfield, Ohio where, at the age of twenty-3 he enrolled for his senior yr of preparatory school at the Wittenberg University, a preparatory school located on the campus of the Wittenberg University. In his time there he performed well, earning good marks and participating in several extracurricular activities. In the spring of 1900 Anderson graduated from the Academy, offering a discourse on Zionism as 1 of the eight students chosen to give a commencement speech communication.[37]

Business, marriage and family [edit]

During his fourth dimension in Springfield, Anderson stayed and worked as a "chore boy" in a boardinghouse called The Oaks among a group of businessmen, educators, and other creatives types many of whom became friendly with the immature Anderson.[37] In particular, a high school teacher named Trillena White and a businessman Harry Simmons played a function in the author's life. The former who was ten years Anderson's senior would walk—raising eyebrows among the other boarders—with the young man in the evenings. More than importantly, according to Anderson, she "showtime introduced me to fine literature"[38] and would later serve as inspiration for a number of his characters including the teacher Kate Swift in Winesburg, Ohio.[39] [40] The latter, who worked as the advertising manager for Mast, Crowell, and Kirkpatrick (later Crowell-Collier Publishing Company, publishers of the Woman's Home Companion) and occasionally took meals at The Oaks, was so impressed past Anderson's get-go voice communication that he offered him a job on the spot every bit an advertising solicitor at his company's Chicago office.[39] Thus, in the summer of 1900, Anderson returned to Chicago where most of his siblings were now living, intent on achieving success in his new white-collar occupation.[41]

Though he performed well, bug with his boss and a dislike for the part routine and for the manner of correspondence, which caused the ultimate rift, caused Anderson to exit Crowell in mid-1901 for a position gear up for him by Marco Marrow, another friend from The Oaks, at the Frank B. White Advertising Company (later the Long-Critchfield Agency).[42] At that place the author stayed until 1906, selling ads and writing advertising re-create for manufacturers of farming implements and articles for the trade journal, Agricultural Advertisement.[43] In this latter magazine Anderson published his offset professional piece of work, a February 1902 piece called "The Farmer Wears Clothes."[44] What followed were approximately 29 articles and essays for his company's magazine, and two for a pocket-sized literary magazine published by the Bobbs-Merrill Company called The Reader.[45] According to scholar Welford Dunaway Taylor, the ii monthly columns ("Rot and Reason" and "Business Types") Anderson wrote for Agricultural Ad exemplified the "grapheme writing" (or character sketches) that would later on become a notable function of the author's approach in Winesburg, Ohio and other works.[46]

"Roof-Set up carried united states of america to Elyria" wrote Sherwood Anderson'due south wife, Cornelia Lane, of the product her husband started a visitor to sell.[47]

Advertising for the Anderson Manufacturing Co., a visitor endemic by Sherwood Anderson from 1907 to 1913, most a decade before he became a well-known author

Role of Anderson'southward job in those early years of his career was making trips to solicit potential clients. On one of these trips around May 1903 he stopped in the abode of a friend from Clyde, Jane "Jennie" Bemis, and then living in Toledo, Ohio. It was at that place that he met Cornelia Pratt Lane (1877–1967), the daughter of wealthy Ohio man of affairs Robert Lane. The two were married a year later, on the 16th of May, in Lucas, Ohio.[48] They would go along to accept three children—Robert Lane (1907–1951), John Sherwood (1908–1995), and Marion (aka Mimi, 1911–1996).[49] Subsequently a short honeymoon, the couple moved into an apartment on the south side of Chicago.[fifty] For 2 additional years, Anderson worked for Long-Critchfield until an opportunity came along from i of the accounts he managed and so on Labor Day 1906, Sherwood Anderson left Chicago for Cleveland to become president of United Factories Company, a mail-guild firm selling various items from surrounding firms.[51]

While his new job, which amounted to the position of sales manager, could be stressful[52] the happy abode life Cornelia had fostered in Chicago continued in Cleveland; "his wife and he entertained oftentimes. They went to church on Sundays, with Anderson decked out in morn clothes and top hat. On occasional Sunday afternoons Cornelia taught him French. She as well helped with his advertising work."[53] Unfortunately, his dwelling house life could non sustain him when ane of the manufacturers United Factories marketed produced a big batch of defective incubators. Soon, letters addressed to Anderson (who personally guaranteed all products sold) began to arrive from customers both drastic and angry. The strain from months of answering hundreds of these letters while continuing his demanding schedule at work and home led to a nervous breakup in the summer of 1907 and eventually his departure from the company.[54]

His failure in Cleveland did non filibuster him for long, nonetheless, because in September 1907, the Andersons moved to Elyria, Ohio, a town of approximately ten thousand residents, where he rented a warehouse inside sight of the railroad and began a mail-order business organisation selling (at a markup of 500%) a preservative pigment called "Roof-Fix".[55] The get-go years in Elyria went very well for Anderson and his family; 2 more than children were added for a full of three in addition to a decorated social life for their parents.[56] Then well, in fact, did the Anderson Manufacturing Co. do that Anderson was able to purchase and blot several like businesses and aggrandize his firm'southward product-lines under the name Anderson Paint Visitor.[57] Carrying on that momentum, in belatedly 1911 Anderson secured the financial bankroll to merge his companies into the American Merchants Company, a profit-sharing/investment firm operating in function on a scheme he developed around that time called "Commercial Democracy".[58] [59]

Nervous breakdown [edit]

It was then, at what seemed the pinnacle of his business achievements, when the stresses of Anderson'due south professional life collided with his social responsibilities and his writing, that Anderson suffered the breakdown that has remained paramount in the "myth"[sixty] or "fable"[61] [62] of his life.[63]

On Thursday, Nov 28, 1912, Anderson came to his function in a slightly nervous country. According to his secretarial assistant, he opened some mail, and in the course of dictating a business concern letter became distracted. After writing a note to his married woman, he murmured something along the lines of "I experience as though my feet were moisture, and they keep getting wetter."[annotation i] and left the part. 4 days afterward, on Sunday, Dec i, a disoriented Anderson entered a drug store on East 152nd Street in Cleveland and asked the pharmacist to assistance figure out his identity. Unable to make out what the breathless Anderson was saying, the pharmacist discovered a phone book on his person and called the number of Edwin Baxter, a member of the Elyria Chamber of Commerce. Baxter came, recognized Anderson, and promptly had him checked into the Huron Road Hospital in downtown Cleveland, where Anderson'due south married woman, whom he would hardly recognize, went to come across him.[64]

Only fifty-fifty earlier returning home, Anderson began his lifelong practice of reinterpreting the story of his breakdown. Despite news reports in the Elyria Evening Telegram and the Cleveland Printing following his comprisal into the hospital that ascribed the cause of the breakdown to "overwork" and that mentioned Anderson's inability to remember what happened,[65] on Dec 6 the story inverse. Suddenly, the breakdown became voluntary. The Evening Telegram reported (possibly spuriously)[66] that "Equally shortly equally he recovers from the trance into which he placed himself, Sherwood Anderson ... will write a book of the sensations he experienced while he wandered over the country as a nomad."[67] This same sense of personal agency is alluded to 30 years later in Sherwood Anderson's Memoirs (1942) where the author wrote of his thought process before walking out: "I wanted to leave, get abroad from business organization. ... Once again I resorted to slickness, to craftiness...The thought occurred to me that if men thought me a lilliputian insane they would forgive me if I lit out...."[68] This thought, however, that Anderson made a conscious decision on Nov 28 to brand a clean break from family unit and business organization is unlikely.[61] [69] [seventy] In the start identify, contrary to what Anderson afterwards claimed, his writing was no undercover. It was known to his wife, secretary, and some business assembly that for several years Anderson had been working on personal writing projects both at nighttime and occasionally in his office at the manufacturing plant.[62] Secondly, although some of the notes he wrote were to himself during his journeying, notes he mailed to his married woman on Sabbatum, addressing the envelope "Cornelia L. Anderson, Pres., American Striving Co.", show that he had some semblance of memory. The full general confusion and frequent incoherence the notes exhibit is unlikely to exist deliberate.[71] While diagnoses for the four days of Anderson's wanderings accept ranged from "amnesia" to "lost identity" to "nervous breakdown", his condition is generally characterized today as a "fugue country."[72] [73] [74] Anderson himself described the episode as "escaping from his materialistic beingness,"[ commendation needed ] and was admired for his action by many young male writers who chose to be inspired past him. Herbert Gold wrote, "He fled in gild to find himself, then prayed to abscond that disease of self, to become 'beautiful and clear.'"[75] [76] After having moved dorsum to Chicago, Anderson formally divorced Cornelia.

Novelist [edit]

Anderson'south first novel, Windy McPherson'south Son, was published in 1916 as part of a three-book bargain with John Lane. This volume, forth with his second novel, Marching Men (1917), are usually considered his "apprentice novels" because they came before Anderson found fame with Winesburg, Ohio (1919) and are generally considered inferior in quality to works that followed.[77]

Anderson'due south most notable work is his drove of interrelated brusque stories, Winesburg, Ohio (1919). In his memoir, he wrote that "Hands", the opening story, was the first "real" story he ever wrote.[78]

"Instead of emphasizing plot and action, Anderson used a uncomplicated, precise, unsentimental style to reveal the frustration, loneliness, and longing in the lives of his characters. These characters are stunted by the narrowness of Midwestern small-town life and by their own limitations."[79]

In addition, Anderson was one of the first American novelists to introduce new insights from psychology, including Freudian assay.[79]

Although his short stories were very successful, Anderson wanted to write novels, which he felt immune a larger scale. In 1920, he published Poor White, which was rather successful. In 1923, Anderson published Many Marriages; in it he explored the new sexual freedom, a theme which he continued in Dark Laughter and later writing.[75] Dark Laughter had its detractors, but the reviews were, on the whole, positive. F. Scott Fitzgerald considered Many Marriages to be Anderson's finest novel.[80]

Beginning in 1924, Sherwood and Elizabeth Prall Anderson moved to New Orleans, where they lived in the historic Pontalba Apartments (540-B St. Peter Street) bordering Jackson Square in the middle of the French Quarter. For a fourth dimension, they entertained William Faulkner, Carl Sandburg, Edmund Wilson and other writers, for whom Anderson was a major influence. Critics trying to ascertain Anderson'southward significance have said he was more influential through this younger generation than through his ain works.[79]

Anderson referred to meeting Faulkner in his cryptic and moving short story, "A Meeting South." His novel Dark Laughter (1925) drew from his New Orleans experiences and continued to explore the new sexual freedom of the 1920s. Although the book was satirized by Ernest Hemingway in his novella The Torrents of Spring, it was a bestseller at the fourth dimension, the just volume of Anderson'south to accomplish that status during his lifetime.

Four marriages [edit]

Anderson and Cornelia Lane married in 1904, had his just 3 children, and divorced in 1916.[81] Anderson chop-chop married the sculptor Tennessee Claflin Mitchell (1874–1929), obtaining a divorce from her in Reno, Nevada in 1924.[82]

In 1924, Anderson married Elizabeth Norma Prall (1884–1976), a friend of Faulkner'due south whom he had met in New York before his divorce from Mitchell.[83] Afterward several years that wedlock also failed, and they divorced in 1932.

In 1928 Anderson became involved with Eleanor Gladys Copenhaver (1896–1985), whom he married in 1933.[84] They traveled and often studied together, and were both agile in the merchandise union movement.[85] Anderson besides became shut to Copenhaver'southward mother, Laura.[86]

Later work [edit]

Anderson oft contributed articles to newspapers. In 1935, he was commissioned to get to Franklin County, Virginia to cover a major federal trial of bootleggers and gangsters, in what was called "The Swell Moonshine Conspiracy". More than xxx men had been indicted for trial. In his article, he said Franklin was the "wettest county in the globe," a phrase used as a championship for a 21st-century novel by Matt Bondurant.[87]

In the 1930s, Anderson published Death in the Woods (brusk stories), Puzzled America (essays), and Kit Brandon: A Portrait (novel). In 1932, Anderson dedicated his novel Beyond Want to Copenhaver. Although by this time he was considered to be less influential overall in American literature, some of what have get his most quoted passages were published in these afterward works. The books were otherwise considered inferior to his earlier ones.

Beyond Desire built on his interest in the trade union movement and was set during the 1929 Loray Mill Strike in Gastonia, North Carolina. Hemingway referred to it satirically in his novel, To Have and Accept Not (1937), where he included as a minor character an author working on a novel of Gastonia.

In his later years, Anderson and Copenhaver lived on his Ripshin Subcontract in Troutdale, Virginia, which he purchased in 1927 for use during summers.[88] While living in that location, he contributed to a country newspaper, columns that were nerveless and published posthumously.[89]

Decease [edit]

Anderson'due south grave mark at Round Hill Cemetery in Marion, Virginia. Designed by Wharton Esherick and executed in black granite by Victor Riu.

Anderson died on March 8, 1941, at the age of 64, taken ill during a cruise to Due south America. He had been feeling abdominal discomfort for a few days, which was later diagnosed as peritonitis. Anderson and his married woman disembarked from the cruise liner Santa Lucia and went to the hospital in Colón, Panama, where he died on March eight.[90] An dissection revealed that a swallowed toothpick had washed internal damage resulting in peritonitis.[91] [92]

Anderson'due south torso was returned to the U.s.a., where he was cached at Round Loma Cemetery in Marion, Virginia. His epitaph reads, "Life, Not Expiry, Is the Bully Gamble".[93]

Legacy and honors [edit]

- In 1971, Anderson's last home in Troutdale, Virginia, known every bit Ripshin Farm, was designated as a National Celebrated Landmark.

- In 2012, Anderson was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[94]

- In 1988 the Sherwood Anderson Foundation was created past the writer's children and grandchildren. It gives grants to emerging writers. The virtually notable of these is the annual Sherwood Anderson Foundation Writers Award. As of 2009, the Foundation'south Co-Presidents were Anderson's grandsons David M. Spear and Michael Spear, and Anderson's granddaughter, Karlyn Spear Shankland was Secretarial assistant. Besides, some great-grandchildren of Anderson served terms in S.A.F. every bit officers and boardmembers: Tippe Miller, Paul Shankland, Susie Spear, Anna McKean, Margo Ross Sears, Abe Spear.

- Michael Spear was besides a copy editor, journalist, and a journalism professor specialized in copy editing at the Academy of Richmond for 34 years, earlier retiring in 2017. David M. Spear is a published author (3 books), retired paper editor, and nationally noted journalist lensman in Madison, Northward Carolina, documenting 2d world nation life in Cuba, Mexico, and rural North Carolina. Karlyn Shankland retired in 1999 from a public schoolteacher career in Greensboro, Due north Carolina after 32 years and earned commendations for her pedagogy.[ citation needed ]

Works [edit]

Beginning edition title folio of Winesburg, Ohio

Novels [edit]

- Windy McPherson's Son (1916)

- Marching Men (1917)

- Poor White (1920)

- Many Marriages (1923)

- Nighttime Laughter (1925)

- Tar: A Midwest Childhood (1926, semi-autobiographical novel)

- Beyond Desire (1932)

- Kit Brandon: A Portrait (1936)

Short story collections [edit]

- Winesburg, Ohio (1919)

- The Triumph of the Egg: A Book of Impressions From American Life in Tales and Poems (1921)

- Horses and Men (1923)

- Death in the Woods and Other Stories (1933)

Poetry [edit]

- Mid-American Chants (1918)

- A New Attestation (1927)[95]

Drama [edit]

- Plays, Winesburg and Others (1937)

Nonfiction [edit]

- A Story Teller's Story (1922, memoir)

- The Modern Author (1925, essays)

- Sherwood Anderson'southward Notebook (1926, memoir)

- Alice and The Lost Novel (1929)

- Hello Towns! (1929, collected newspaper articles)

- Nearer the Grass Roots (1929, essays)

- The American Canton Fair (1930, essays)

- Possibly Women (1931, essays)

- No Swank (1934, essays)

- Puzzled America (1935, essays)

- A Writer'southward Conception of Realism (1939, essays)

- Dwelling Town (1940, photographs and commentary)

Published posthumously [edit]

- Sherwood Anderson'southward Memoirs (1942)

- The Sherwood Anderson Reader, edited by Paul Rosenfeld (1947)

- The Portable Sherwood Anderson, edited by Horace Gregory (1949)

- Letters of Sherwood Anderson, edited by Howard Mumford Jones and Walter B. Rideout (1953)

- Sherwood Anderson: Brusk Stories, edited by Maxwell Geismar (1962)

- Render to Winesburg: Selections from Iv Years of Writing for a State Newspaper, edited past Ray Lewis White (1967)

- The Buck Fever Papers, edited by Welford Dunaway Taylor (1971, collected newspaper manufactures)

- Sherwood Anderson and Gertrude Stein: Correspondence and Personal Essays, edited by Ray Lewis White (1972)

- The "Author'south Book," edited past Martha Mulroy Back-scratch (1975, unpublished works)

- France and Sherwood Anderson: Paris Notebook, 1921, edited past Michael Fanning (1976)

- Sherwood Anderson: The Author at His Arts and crafts, edited by Jack Salzman, David D. Anderson, and Kichinosuke Ohashi (1979)

- A Teller'southward Tales, selected and introduced by Frank Gado (1983)

- Sherwood Anderson: Selected Letters: 1916–1933, edited by Charles E. Modlin (1984)

- Letters to Bab: Sherwood Anderson to Marietta D. Finely, 1916–1933, edited by William A. Sutton (1985)

- The Sherwood Anderson Diaries, 1936–1941, edited by Hilbert H. Campbell (1987)

- Sherwood Anderson: Early Writings, edited past Ray Lewis White (1989)

- Sherwood Anderson's Love Letters to Eleanor Copenhaver Anderson, edited by Charles East. Modlin (1989)

- Sherwood Anderson's Secret Love Letters, edited past Ray Lewis White (1991)

- Certain Things Last: The Selected Stories of Sherwood Anderson, edited by Charles East. Modlin (1992)

- Southern Odyssey: Selected Writings by Sherwood Anderson, edited by Welford Dunaway Taylor and Charles Due east. Modlin (1997)

- The Egg and Other Stories, edited with an introduction by Charles E. Modlin (1998)

- Collected Stories, edited by Charles Baxter (2012)

Notes [edit]

- ^ The quote higher up comes from the Frances Shute, Anderson's secretary at the time, as cited in Rideout (2006), 155. In Anderson (1924), it was remembered as "I have been wading in a long river and my anxiety are wet. My feet are cold, moisture and heavy from long wading in a river. At present I shall get walk on dry state", whereas in Anderson (1942), information technology was "My anxiety are cold and moisture. I have been walking too long on the bed of a river."

References [edit]

- ^ Anderson, Sherwood (1876–1941) | St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture Summary

- ^ Sherwood Anderson, Camden, OH Birthplace - Newspapers.com

- ^ a b c Rideout (2006), 16

- ^ Schevill (1951), eight

- ^ Howe (1951), 12

- ^ Townsend (1987), iii

- ^ Rideout (2006), xviii

- ^ a b Rideout (2006), 20. For connectedness between Tar and Caledonia, also encounter Anderson (1942), 14–16

- ^ Townsend (1987), iv

- ^ Howe (1951), thirteen–fourteen

- ^ Rideout (2006), 34

- ^ a b Townsend (1987), xiv. The chapter nigh Anderson's early on life is called "Jobby".

- ^ a b c Howe (1951), sixteen

- ^ Rideout (2006), 39

- ^ Townsend (1987), 25–26

- ^ Rideout (2006), 37–38. Encounter Anderson (1924), 155–56 for listing of authors enjoyed past young Anderson

- ^ Townsend (1987), 11

- ^ Spanierman Gallery, LLC. KARL ANDERSON (1874 - 1956) Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 26 May 2013.

- ^ Townsend (1987), 28

- ^ Rideout (2006), 59–61

- ^ a b Townsend (1987), thirty

- ^ Rideout (2006), l

- ^ Rideout (2006), 47

- ^ Townsend (1987), 31

- ^ Howe (1951), 27

- ^ Rideout (2006), 69–71

- ^ Townsend (1987), 33

- ^ Townsend (1987), 34

- ^ Anderson (1942), 112

- ^ a b Rideout (2006), 73–74

- ^ Townsend (1987), 36

- ^ Townsend (1987), 38

- ^ Rideout (2006), 78

- ^ Townsend (1987), 39–41

- ^ Howe (1951), 29

- ^ Townsend (1987), 41

- ^ a b Howe (1951), 31–32

- ^ Anderson (1984), 227–228

- ^ a b Townsend (1987), 42–43

- ^ Rideout (2006), 226

- ^ Rideout (2006), 92–93

- ^ Daugherty (1948), 31

- ^ See Rideout (2006), 95–110 & Anderson (1989) for assay and the nerveless early work, respectively

- ^ Rideout (2006), 95

- ^ Campbell, Hilbert H (Summer 1998). "The Early not-Periodical Writings". The Sherwood Anderson Review 23 (2).

- ^ Taylor, Welford Dunaway (Winter 1998). "Remembered "Characters" in Winesburg, Ohio". The Winesburg Eagle 23 (1).

- ^ Rideout(2006), 133

- ^ Ohio, County Marriages, 1774-1993

- ^ Rideout (2006), 112–114

- ^ A copy of Sherwood Anderson's honeymoon journal is available in the Sherwood Anderson Review (Summertime 1998)

- ^ Rideout (2006), 122–123

- ^ Townsend (1987), 59–60

- ^ Schevill (1951), 45

- ^ Rideout (2006), 126–128

- ^ Daugherty (1948), 33

- ^ Howe (1951), 41–42

- ^ Rideout (2006), 134

- ^ Rideout (2006), 137–138

- ^ Sutton (1967), ix–12

- ^ Schevill (1951), 55

- ^ a b Howe (1951), 49

- ^ a b White (1972), xii–xiv

- ^ Rideout (2006), 149–155

- ^ About Anderson's biographers agree on the events included here. For a general sense, see Rideout (2006), 155–156; Schevill (1951), 52–59; Townsend (1987), 76–82.

- ^ See bug of December 2nd and 3rd for the erstwhile and December 3rd for the latter

- ^ Sutton (1967), 43–44

- ^ Elyria Evening Telegram(06 Dec 1912) equally quoted in Schevill (1951), 59

- ^ Anderson (1942), 194

- ^ Sutton (1967), 12

- ^ Rideout (2006), 157

- ^ Sutton (1967), 36–39 offers the complete text of the notes with assay, and several other biographers including Townsend (1987) and Rideout (2006) clarify and print selections.

- ^ Townsend (1987), 81

- ^ Sperber, Michael (05 June 2013). "[Dissociative Amnesia (Psychogenic Fugue) and a Literary Masterpiece http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/psychogenic-fugue-literature]" Psychiatric Times. Accessed 11 Nov 2013.

- ^ Ridout (2006), 156–157

- ^ a b Balakian, Nona (x July 1988). "A Life of Nighttime Laughter". The New York Times. Accessed 31 May 2013.

- ^ Gold (1957–1958), 548

- ^ Howe (1951), 91

- ^ Anderson, Sherwood. Sherwood Anderson's Memoirs. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1942.

- ^ a b c Daniel Mark Fogel,"Sherwood Anderson", The American Novel, PBS, 2007, accessed 2 June 2013

- ^ Howe, Irving. Sherwood Anderson. New York: William Sloane Associates, 1951. (pg. 254)

- ^ "Sherwood Anderson's Biography". umich.edu. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Bassett (2005), p. 21

- ^ Anderson, Elizabeth and Gerald R. Kelly (1969). Miss Elizabeth. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- ^ Anderson (1991), pp. 8–nine

- ^ Documenting the American South: Oral Histories of the American South, Academy of North Carolina

- ^ "Virginia Women in History 2007: Laura Lu Scherer Copenhaver".

- ^ Fisher, Ann H. (seven/1/2008). "The Wettest Country in the World [Review]". Library Journal. 133 (12): 58.

- ^ "Ripshin Farm". National Historic Landmark summary list. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June vi, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ Return to Winesburg: Selections from Iv Years of Writing for a State Newspaper, edited by Ray Lewis White (1967)

- ^ "Anderson Is Dead; Noted Author; 64". New York Times, 9 March 1941, p. 41.

- ^ Walter B. Rideout (February fifteen, 2007). Sherwood Anderson: A Writer in America, Volume 2. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 400–. ISBN978-0-299-22023-5.

- ^ Irving Howe (1951). Sherwood Anderson. Sloane. pp. 241–. ISBN978-0-8047-0236-ii.

- ^ "Sherwood Anderson". findagrave.com. Accessed April 22, 2012.

- ^ "Sherwood Anderson". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2012. Retrieved October viii, 2017.

- ^ Howe (1951), 208

Sources [edit]

- Anderson, Elizabeth and Gerald R. Kelly (1969). "Miss Elizabeth". Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Anderson, Sherwood (1924). A Story Teller'south Story. New York: B.W. Huebsch.

- Anderson, Sherwood (1942). Sherwood Anderson's Memoirs. New York: Harcourt, Caryatid and Visitor.

- Anderson, Sherwood (1984). Sherwood Anderson: Selected Letters. Edited by Charles Modlin. Knoxville, TN: Tennessee Up. ISBN 9780870494048

- Anderson, Sherwood (1989). Early Writings. Ed. Ray Lewis White. Kent and London: Kent State Upwards, 1989. ISBN 0873383745

- Anderson, Sherwood (1991). Sherwood Anderson's Surreptitious Beloved Letters. Edited by Ray Lewis White. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press. ISBN 9780807125021

- Bassett, John Earl (2005). Sherwood Anderson: An American Career. Plainsboro, NJ: Susquehanna Upwardly. ISBN 1-57591-102-7

- Cox, Leland H., Jr. (1980), "Sherwood Anderson", American Writers in Paris, 1920–1939, Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 4, Detroit, Mich.: Gale Research Co.

- Daugherty, George H. (Dec 1948). "Anderson, Advertising Homo". The Newberry Library Bulletin. 2d Series, No. 2.

- Gilt, Herbert (Winter, 1957-1958). "The Purity and Cunning of Sherwood Anderson". The Hudson Review 10 (four): 548–557.

- Howe, Irving (1951). Sherwood Anderson. New York: William Sloane Assembly.

- Rideout, Walter B. (2006). Sherwood Anderson: A Writer in America, Volume 1. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21530-9

- Schevill, James (1951). Sherwood Anderson: His Life and Piece of work. Denver, CO: Academy of Denver Press.

- Sutton, William A. (1967). Go out to Elsinore. Muncie, IN: Ball State UP.

- Townsend, Kim (1987). Sherwood Anderson: A Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36533-3

- White, Ray Lewis (1972). "Introduction". in White, Ray Lewis (ed). Marching Men. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve Academy. ISBN 0-8295-0216-5

External links [edit]

- Works by Sherwood Anderson in eBook course at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Sherwood Anderson at Projection Gutenberg

- Works past Sherwood Anderson at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Works past or about Sherwood Anderson at Internet Annal

- Works by Sherwood Anderson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sherwood Anderson Biography

- Sherwood Anderson Biography 2

- Sherwood Anderson in the Dial

- Sherwood Anderson Links

- Winesburg, Ohio hypertext from American Studies at the Academy of Virginia.

- The Triumph of the Egg hypertext from American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- Oral History Interview with Eleanor Copenhaver Anderson from Oral Histories of the American South

- Sherwood Anderson Papers at The Newberry Library

- Sherwood Anderson Annal at the Smyth-Bland Regional Library

- Sherwood Anderson Literary Middle

- Ten Stories past Sherwood Anderson read aloud past contemporary writers including Charles Baxter, Deborah Eisenberg, Robert Boswell, Patricia Hampl, Siri Hustvedt, Ben Marcus, Rick Moody, Antonya Nelson and Benjamin Taylor

- I am a fool Persian Translation, E-Volume at Taaghche.ir

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: ernestineevelostrues.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Sherwood Anderson A Story Teller's Story Download UPDATED"

Post a Comment